The public life of women in photos, a song and the news

TK#2: a photo exhibition from Nepal, a song about a South African singer-activist, and thoughts on gender gap in the news sources

Dear Readers,

I’d like to begin by thanking everyone for subscribing to this Substack. Your support means a lot and has definitely encouraged me to write the second edition of this newsletter on time when I’ve had little time to spare. At this moment, I am chasing a deadline for a story on gender-based violence and need a long nap! If you are new here and wondering what TK means—check out the About page or the last newsletter.

TLDR: TK stands for “To Come” and is often used by journalists and editors, mostly in the West, to indicate material that needs to be filled in. So when I don’t know a source’s name when writing a story, I will write “According to TKTK…”. On why I call my Substack TK, read this.

So today on TK, I have three segments: a snapshot of a photo exhibition from Nepal that really moved me; the fascinating story behind the Instagram-famous earworm Makeba; and thoughts on efforts to reduce the gender imbalance in my stories.

This year…

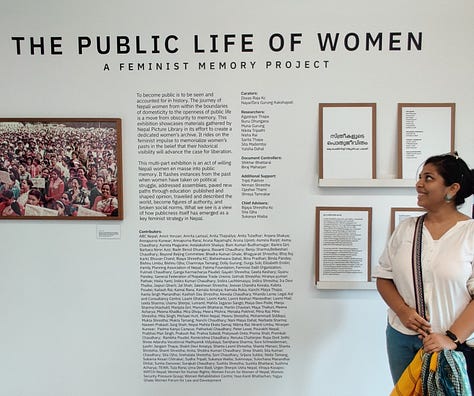

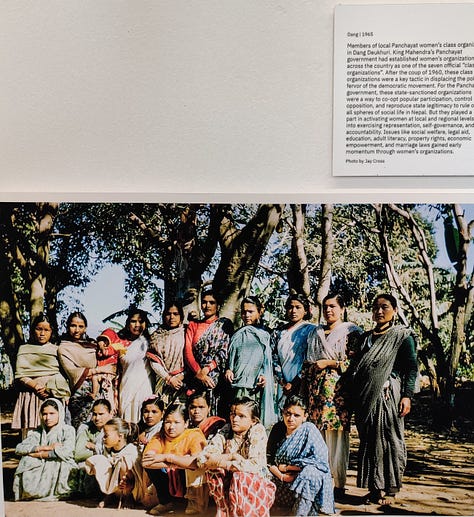

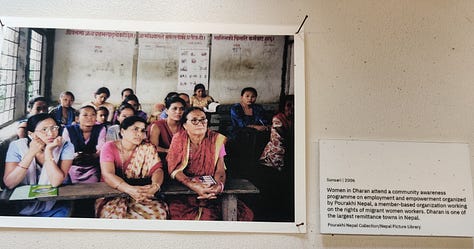

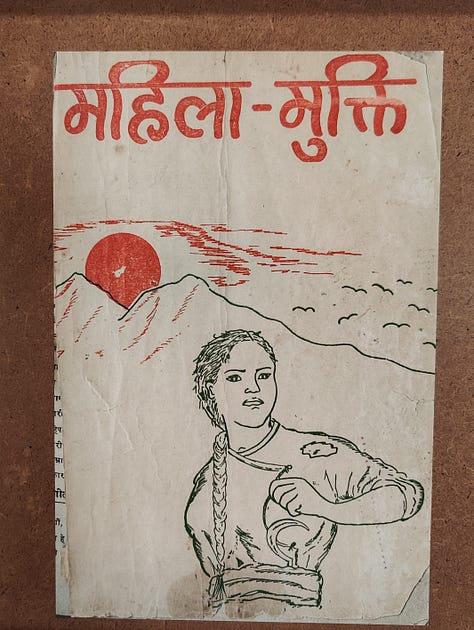

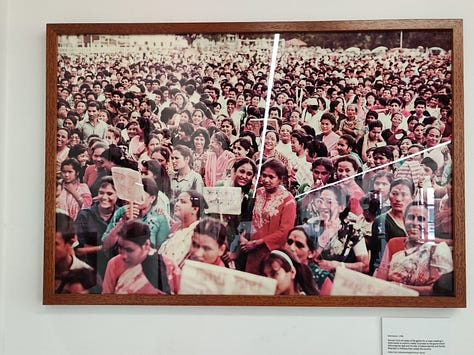

…I visited the Kochi Muziris Biennale, an art festival spread across this small coastal city in Kerala. At the Pepper House, one of the exhibition venues, a large hallway was dedicated to photos of the everyday lives of Nepali women. Photos of women in rallies, protest marches, passports, gatherings, meetings, family portraits, and many more.

Nepal is often overshadowed by neighbours India and China, geographically, politically, and in the media too. So what about its women? We learn as the exhibition moves from studio portraits of the mid-20th century to black-and-white reel photos, and finally coloured images, that Nepali women have played a pivotal role in shaping the country's destiny.

The exhibit, called The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project, is curated by Nayantara Kakshapati and Dewas Raja KC from the Kathmandu-based Nepal Picture Library. This facility has collected some 125,000 images and several testimonies of women in the public sphere for several years. A few hundred of them are on display.

The a description of the exhibition read:

To become public is to be seen and accounted for in history. The journey of Nepali women from within the boundaries of domesticity to the openness of public life is a move from obscurity to memory.

I tried to reach the curators for an interview for a story but that did not work out.

If you can’t visit the exhibition, which last I checked was touring Istanbul, you can read this blog. It has a comprehensive and decent overview of parts of The Public Life of Women, along with pictures.

This soundtrack…

… kept coming up on Instagram reels. Makeba by Jain–not the Marwari-Gujarati Jain you probably just imagined–is a French singer-songwriter.

It has been used 4.1 million times on Instagram and has 197 million views on YouTube since it was released six years ago. I was curious who Jain was singing about, and it led me–and by now many others–to Miriam Makeba, a South African artist, musician, singer, and anti-apartheid activist.

Jain, in her song, coos:

I want to see you sing / I want to see you fight / Because you are the real beauty of human rights.

Makeba rose to fame after her speeches at the United Nations in 1963 and 1976. She also appeared in the documentary Come Back Africa, which depicted the harsh conditions in her country. As a consequence, she was banned from returning by the apartheid state. Historians have said she combined her music with civil rights activism, introducing the West to African music, and shaping the Afro look. Also known as ‘Mama Africa,’ she was the first African to win a Grammy.

I can admit, I finally learned something thanks to Instagram reels. I also found these interesting profiles of Makeba in The Conversation and Christian Science Monitor.

The first time…

…I wrote for BBC Travel, the editor told me I should aim for a 50:50 gender balance in the story. If I quoted two men, I had to quote two women. The story was from Slovenia and had nothing to do with gender [about the birth of nature-healing and wellness travel in Europe]. The editor directed me to the BBC’s 50:50 The Equality Project, which is committed “to consistently create journalism and media content that fairly represents our world.” Organisations across the world, which are part of this project, aim towards gender parity in sources.

Women make up fewer than one in four (24%) of people that are heard, read or seen in newspaper, television, and radio news, and the gender gap is most evident when it comes to ‘serious’ journalism such as political and government-related news, according to the Global Media Monitoring Project. In India, things are equally bad.

There are several reasons for this, and one of the main ones is that journalists turn to male sources because they are easily accessible, and they dominate various fields. Sociologist Gaye Tuchman says women are being “symbolically annihilated” in the media.

Ed Yong, a science journalist at The Atlantic, while documenting his efforts to reduce the gender imbalance in histories, pointed out that he contacted 1.3 men to get one male quote, and around 1.6 women to get one female one. He reasons that women may be a minority in the field they work in, and are thus overburdened with work and demands on their time. Another reason, he writes:

Second, I suspect women may be more likely than men to decline an interview on the assumption that they aren’t the right fit–something I have anecdotally experienced but haven’t rigorously quantified.

I find the second reason hard to believe. Over the years, I have tried to maintain the gender balance in most of my stories (there are times I have failed). People have asked me if it’s hard to find female sources–particularly experts–, and it really is not. Yes, it takes a little extra time. But has any woman expert turned down an interview because she didn’t think she was the right fit? Not once. I obviously have less experience than Yong and others who have shared this as a concern, and I may be wrong. But like Yong, I too would appreciate some rigorous research.

A few months ago, a commissioning editor at the digital division of a global newspaper told me that they found it hard to find sources who were women or from marginalised communities in the Global South. Access, they said, was hard.

This reveals more about the publication and the reporters’ access to sources. Perhaps the reporters were White, from the West, or in the case of India, upper caste men? For a story on the importance of non-Western journalists reporting in local languages, Chinese journalist Jane Qiu told me that journalists from the West reporting on China do not understand the language, and also the social and political context.

The same, I thought, can be said of a certain section of reporters trying to fix the gender imbalance in stories from the Global South. Journalism is a field dominated by men: perhaps there is a need to first understand the social and cultural contexts in which women live and work in these countries. Qiu called for capacity building of journalists in the Global South to cover global science stories. Perhaps the same needs to be done for gender?

I have found that it does take a little effort to identify the right female sources, particularly from rural, poor or marginalised communities. What works is a combination of planning, networking at the grassroots level and sensitivity to their social and cultural norms.

In my experience, women are generous with their time and want to be heard; sometimes one may need to go to them and have a chai before they open up.

Being mindful of their circumstances goes a long way. For instance, women in rural areas are not glued to their phones and may not have one. So phone interviews are not an option. They also get spooked when I call them after a field visit. I have learnt it is best to get everything done when on the ground. This, of course, is a problem for journalists working with some Western publications, who have an extensive fact-checking process and may call the sources for verification. This then poses the question–shouldn’t the editorial and fact checking processes also be sensitive?

I have not rigorously studied and analysed my stories like Yong and others do. But for every story, I do try to speak to and quote women. Even when no other commissioning editor, apart from that one person at BBC, asked me to follow the 50:50 principle. In some stories, I managed to quote only female sources. I don’t see that as wrong: for a long time we were perfectly fine with only quoting men, why should this be a cause for concern?

I do want to make my stories more inclusive. And I second Yong’s ambition:

I’m thinking about how to include more voices from LGBTQ, disabled, or immigrant communities. I’m thinking about the people who appear in the photos that accompany my pieces, rather than just those whose words appear within quote marks. Gender parity is a start, not an end point.

If you are a journalist wanting to reduce the gender gap in your stories, read this story in The Open Notebook on making your writing transgender inclusive, and this one on improving diversity of sources. NPR maintains a Diverse Sources database. There are several other resources listed here.

That’s it from me for today. Hope you’ll stick around for the next edition. And if you are new and liked reading this newsletter, do subscribe and spread the word!

Best,

Mahima Jain