How caste worsens climate impacts, affects disaster relief and rehabilitation efforts

TK#13 is part 1 of notes from a Water Journalists' Roundtable. Climate change impacts have a uniquely Indian layer: the caste geography in Indian villages and cities

I was recently invited to a Water Journalists Roundtable hosted by the Science Media Center at IISER Pune. When I received the invitation from Dr Shalini Sharma, Associate Professor at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at IISER Pune and head of the Science Media Center, the first thing I had to do was take a look at my work and examine how much of it was “water reporting.” I quickly realised water ran through many of my stories. Many journalists who attended the roundtable admitted this realisation was recent and post facto. Water had come up quite naturally in our coverage of many issues, we all realised. I had to make a short presentation about my coverage in particular; here’s a longer version of that presentation and reflections from my work. (This edition will contain extensive excerpts from my past work in order to make my point.)

TK, short for “To Come,” in publishing and journalism is used by editors to mark missing information. This is Mahima Jain’s newsletter where she shares marginalia from her reporter’s diary and research. Previous editions have covered Indira Gandhi’s environmental policies, FAQs on how to write journalism grant applications and more. Subscribe to get more posts.

I came across the caste geography of Indian villages sometime in my teens, though I didn’t have a vocabulary for it then. (I am aware it reflects a certain caste privilege to only “learn” of caste during one’s teens). I grew up in Chennai, but as a child I often visited my ancestral village in Rajasthan. There I found that the “main street” of the village, around the Jain temple, was deserted. Empty locked up houses street after street.

Everyone’s left for the cities, some of the last remaining occupants told me. But I learnt that over 6,000 people inhabited the village. Where did they all live, I wondered? On the “outskirts”, conversations with my grandparents revealed.

It was during my first few visits to more villages as a journalism student that I further understood this was the caste geography of Indian villages. Thanks to Prof. K. Nagaraj, formerly with Madras Institute of Development Studies and professor at the Asian College of Journalism, I read up on the work of Andre Beteille, John Harriss (Slater’s Villages), and others.

At the inaugural lecture of this event, veteran journalist P. Sainath reminded us that the geography of caste in Indian villages is really about water and arable land. In my reporting on climate change and disasters, I have stumbled upon yet another aspect to this: there’s a geography of caste in disaster relief, rehabilitation and resilience as well. Climate change impacts in India can potentially be better or worse depending on someone’s caste. And this in turn is fundamentally tied to access to water and land ownership.

Climate disasters can be categorised as rapid onset and slow onset. Cyclones, hurricanes, flash floods are rapid onset disasters. Droughts, sea level rise, and erosion are slow onset. Most rapid onset disasters are water-based. Given that the government response to climate events is still largely reactive, with little to no long-term planning to manage the crisis ahead, the rapid onset water-based disasters get the lion’s share of the policy and financial attention.

We’ve enough evidence to show India will continue to suffer more intense cyclones, storm surges, tidal waves, saline water intrusion, sea level rise, and other effects of climate change in the coming years. Currently, 17% of all Indians (250 million) live 50 km from the coast. Of the country’s 7,500 km long coastline, 5,700 km is prone to cyclones and tsunamis, with the east coast being more vulnerable than the west.

India prides itself on rapid disaster relief. Many of its states have a string of relief camps along the coast and robust early warning systems for cyclones. But examine the response to the disaster itself and you’ll see the crucial steps of long-term rehabilitation and resilience to withstand more such events in both rural and urban areas are missing. The way villages and cities are organised mean that after a disaster or some prolonged climatic event, people of the ‘lowest’ castes and classes are routinely displaced more easily, find themselves out of jobs for longer periods, and receive less compensation (since most agricultural compensation is tied to land ownership). Disaster relief too often focuses first on the ‘upper’ caste areas of a village. Reports of upper caste inhabitants blocking distribution of aid to lower caste areas aren’t uncommon.

I reported on Cyclone Fani that hit several districts in Odisha in 2019. It destroyed coconut, banana and paddy farms, and polluted the water supply. Access to and contamination of freshwater post-disaster affects the poorest first; inundation and salination of farms after storm surges affects land owners as well as farm labourers. But it's the land-owners who are compensated, not the tenants or labourers. (Read coverage of Cyclone Fani and Gaja for IndiaSpend here and here)

“Since Fani, I have no money to make ends meet, we have no food, water, or shelter,” Sridhar Sethi, a landless SC farmer from Talamala, Puri District, Odisha, told me then.

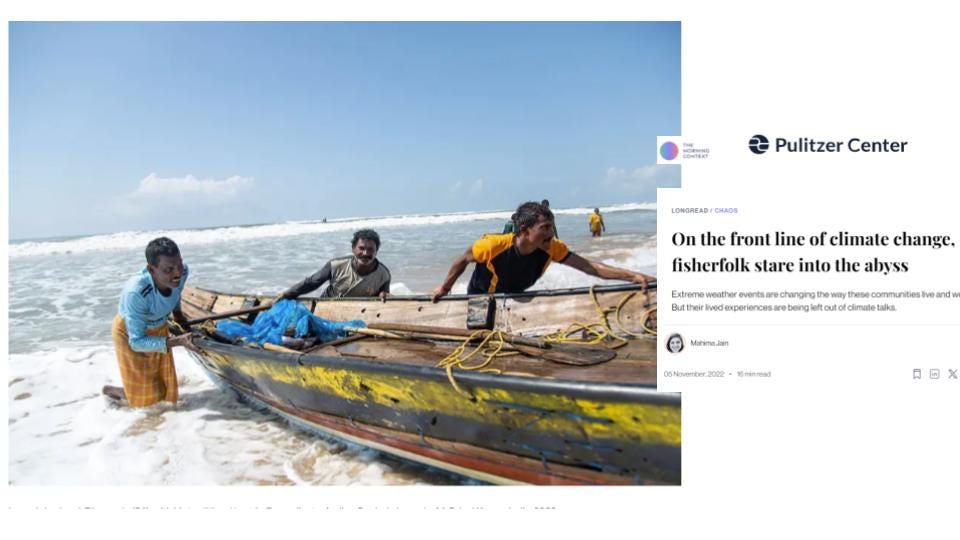

Fisherfolk are uniquely affected too. Coastal areas experience more cyclones–or even red alert days–than before, leading to loss of fishing days and damage to fishers’ properties.

After Cyclone Gaja in 2018 and Cyclone Nivar in 2020, fisherfolk told me about sand and sludge damaging boats anchored on the shores. (My report on Cyclone Nivar for Mongabay here.)

“We kept moving the nets and boats inland but the seawater intrusion and the winds kept increasing. The indirect damage to their livelihood is being ignored. The storm surge was the worst I’ve ever seen,” said Bharathi, president, South India Fishermen Welfare Association, after Cyclone Nivar hit Chennai in 2020.

While reporting in Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh in 2022 (my report on fisheries sector and impact of heat for The Morning Context here, the story was nominated for Mumbai Press Club Red Ink award), boat owners and migrant fisherfolk said this was severely affecting their work and income. The state only compensates for property damaged in cyclones, some told me. When a boat owner invests money, fuel and labour for a fishing expedition (in Gujarat this can be INR 3-4 lakh per trip) but has to make unscheduled halts due to unseasonal rough weather, they lose that investment and can’t recover it.

Then there are the informal workers, often women, who work in fish processing and supply chains across India who witness a whole different kind of impact due to water-based disasters as well as heat. They have limited access to water or technology or safe working conditions that can help them adapt to increasing temperatures.

In 2022, I met Rajamma, who is among 380 million Indian workers (both in fisheries and in other sectors) who work outdoors in the heat. Such heat-exposed labour contributes about 50% of India’s GDP. Declining labour productivity owing to heat could cost the country 2.5-3.5% of its GDP by 2030. Rajamma walks for miles to sell fishes, which she purchases from artisanal fishermen from her village. She walks for over 7-10 hours each day in heat, carrying a load the size of a check-in bag. She’s suffered heat strokes, and most of her friends have kidney stones. Through the day her access to clean drinking water is less than ideal and she rarely carries a water bottle.

In Rajasthan, during the unbearable heatwave of 2022, Bhuri developed a severe stomach ache. She is a widow who does menial jobs. She was unable to fetch water for herself and ran out of groceries. After a visit to a private clinic and spending INR 4,000 on scans, she was told she had kidney stones.

Heatwaves trigger dehydration and studies show lack of access to potable water is linked to a higher prevalence of kidney stones. While there may have been other causes, no one around Bhuri told her heat could have contributed to this. She was given generic advice: “Drink more water.”

I found social protection and workfare programmes like MGNREGA are crucial to address loss of work for women, particularly after climate events such as cyclones and heatwaves, but here too there’s a disparity in the way the government reacts to climate events. (Read my story for Mongabay.)

“The government immediately offers extra MGNREGS working days and other relief support after “head-line grabbing” water-based events such as post-floods or cyclones. No such announcements are made through slow-onset events such as droughts, which go unreported in most cases,” said Dr Ritu Bharadwaj, a researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development.

In more than a decade of heatwaves that Rajasthan has suffered, the government has never offered compensation for lost wages or work. Drought-hit areas are entitled to 50 additional days of work under the scheme — but this isn’t implemented. There have been year-long delays in declaring droughts and budget cuts too, Mukesh Goswami of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), said.

Bharadwaj has found that people move because of slow-onset disasters like droughts and rising sea levels as well as rapid onset disasters like cyclones, floods and hurricanes. But it's the slow onset disasters that result in higher levels of migration and increased levels of poverty.

Most men in Bhuri’s village have moved as also the men in Rajamma’s village. Rajamma’s husband has become a migrant fisher in the West coast of India as the fish catch in the sea around her village could no longer sustain a family of five, she said.

Trafficking of women and girls is significantly higher in places that witness slow onset disasters as well, Bharadwaj has found.

Caste-based impact of climate change follows migrants into the cities. Rapid urbanisation makes climate variabilities worse as seen in Bengaluru and Chennai, both cities that witness cycles of flooding and water shortages.

“When there are heavy rains, winds and storm surges all acting together, there is no way for the water to flush out into the sea because the sea water is pushing in as the rainwater pushes out. Such compound events can cause flooding,” said Roxy Koll, a scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in Pune.

For instance, Chennai’s wetlands have nearly vanished. After every cyclone or monsoon, the water reminds us that we’ve encroached freshwater ecosystems.

Once there were 6,000 lakes and reservoirs in Chennai and its two neighbouring districts of Kanchipuram and Tiruvallur, collectively known as the ‘yeri’ (lake in Tamil) districts. However, land-use conversion for residential flats and housing colonies destroyed 2,104 water bodies.

Most often the densely populated urban slums, where the working class and poor live, experience prolonged water-logging, flooding, water contamination and other impacts of cyclones and flooding.

In 2019, I met Pratima Sagar Das in a village in Odisha. She belongs to a ‘lower’ caste and has barely any assets. In the Super Cyclone of 1999, she was heavily pregnant with her third child. She lost all her belongings and the event pushed her family further into poverty. Soon after the cyclone, she gave birth to a boy and named him Pralay, which means ‘storm’, perhaps in the memory of the cyclone that took so much from her.

By 2018, Kuber, her eldest, had moved to Pondicherry to work as a migrant labourer. There he lived in a tin shed on a terrace with many other workers. In late 2018, Pondicherry was hit by cyclone Gaja. Kuber was displaced and lost his job due to the storm’s aftereffects. He returned home shortly after, only to witness Fani in 2019. Pratima and her children once again suffered extensive damage to their house, small farm land, livestock and other belongings.

Between 1891 and 2006, 308 cyclones crossed the east coast, of which 103 were severe (Gaja’s winds at 140 kmph put the storm in the “very severe” category; Fani managed 260 kmph and was “extremely severe”). The west coast experienced weaker cyclonic activity: of the 48 cyclones, 24 were severe. But activity on the west coast is picking up, recent evidence shows.

Not only are the poor and vulnerable classes more likely to suffer during a disaster but because they experience slower income growth, they also have a harder time recovering. Between 2 million and 50 million Indians may be pushed into poverty by 2030 for these reasons, according to a UN report on climate change and poverty, which warned of a “climate apartheid”.

Rajamma, Bhuri, Pratima Sagar Das, Pralay, Kuber all belong to one of the many ‘lower’ or other ‘backward’ castes. They have witnessed generational poverty and continue to suffer because of systemic inequity worsened by climate change.

There may be more ways in which the caste geography of India’s villages is worsening the consequences of climate change, resulting in inadequate relief, rehabilitation and resilience.

***

In Part 2, I will share takeaways from Water Journalists’ Roundtable. Subscribe to get the next edition in your inbox. Get in touch write[at]mahimajain[dot]in.

Best,

Mahima Jain

Thanks for reading TK: Mahima Jain’s Substack! Those who are new here: I am Mahima Jain, an award-winning independent journalist covering the socio-economics of gender, environment and health. You can see some of my work here: www.mahimajain.in.