11 years after Nirbhaya case: What have we done to tackle violence against women?

India promised harsher laws and stricter punishments for perpetrators of gender-based violence, but what about survivors? This year, I embarked on a reporting project to cover survivors' needs.

TK #6

Dear readers,

Sorry I’ve been AWOL.

It’s been several weeks–perhaps months?--since I sent out a newsletter, and a lot has happened in that time. I was travelling for work and for leisure, then there was a round of viral fever, festivities and more work. So here I am, just another writer, standing in front of her readers, asking them to trust her commitment to her work and this newsletter… [It’s the holiday season–and this is a Notting Hill reference.]

But as one editor I work with very kindly said, you need to stop being hard on yourself and just do it. So here I am, and I will jump straight to the point. In this edition of TK, let us talk about the rape case that shook India.

On Saturday, December 16, we mark 11 years since the night Jyoti Singh–or Nirbhaya–was raped on a moving bus by four men. She later died of her injuries. People across India–and the world–were outraged, and demanded change. I remember the massive protests that rocked the country that winter. It felt like women’s safety was finally a headline-grabbing event. We were forced to confront the reality that Indian girls and women live in fear, every minute of every day. It may sound bleak, but we are never really free.

Over the next few years, we did see some change. It was mostly in the form of harsher punishments and stricter laws for perpetrators. The government poured money into some infrastructure for women. But I kept hearing that whatever was being done to address the epidemic of violence faced by women wasn’t enough. We need more focus on the needs of the survivor. So on the 11th anniversary of Nirbhaya, I am sharing something I worked on this year.

Earlier in 2023, I applied for a Pulitzer Center grant to report on how India treats survivors of gender-based violence. I had been pitching editors since late 2022, and everyone seemed to like the idea but somehow wouldn’t commission longform pieces. Finally, editors at Scroll, Missing Perspectives, Suno India and The Wire saw that these were important stories. The Pulitzer Center was keen. Everyone was on board a couple of months into 2023. I had plans to report across three different states: Karnataka, Gujarat, Maharashtra. This was my project outline:

India's Struggle Toward Health Care for Survivors of Gender-Based Violence

There is a systemic gender gap in access to health care in India. Only 37% of Indian women access health services, accounting for abysmally low health care expenditures.The percentage of survivors of gender-based violence seeking health care is far lower. Even with only 1% of reported cases, India records high levels of gender-based violence; 99% of such cases fall through the cracks. One of the main reasons for that is the lack of gender mainstreaming—integrating a gender equality perspective at all levels of policies, programs, and projects—in the health care sector. High levels of gender-based violence and poor access to health care are intrinsically related.

India promised gender-focused reforms in the criminal justice and health sectors after the 2012 Delhi Gang Rape. While the criminal justice system saw some changes, it did not address the health care needs of gender-based violence survivors, which include social and psychological support, first aid, long-term care, and financial aid.

A decade on, the government's promises to keep women safe have failed on many fronts. This series will investigate how India's health care system can and should respond to survivors of violence.

I reported for this over the summer, spoke to more than 35 healthcare providers–doctors, nurses, hospital administrators, coordinators, ASHA workers, in more than eight hospitals across these states. I also interviewed survivors.

This week, the final piece of this series came out. You can see the entire project at the Pulitzer Center here. Below, I introduce the pieces with a short Q&A followed by a brief outline. Please read or save for later, and share with people who may find this useful!

Can hospitals really help survivors of gender-based violence?

Yes.

Doctors and nurses play a vital role in identifying survivors of violence. Anyone who’s been abused will seek care, and the abuse often leaves a mental or physical mark on one’s body–doctors can be trained to look for these signs and symptoms. The World Health Organization emphasises the role of hospitals in tackling violence against women. But centrally, India doesn’t have any programmes to strengthen healthcare providers’ capacity to treat survivors of violence. We don’t even have it in our medical curricula.

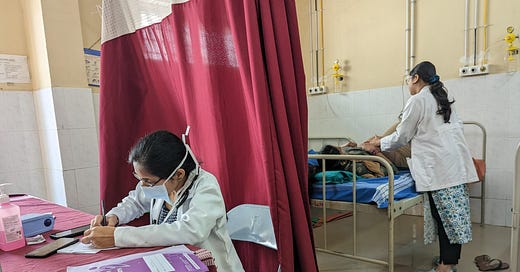

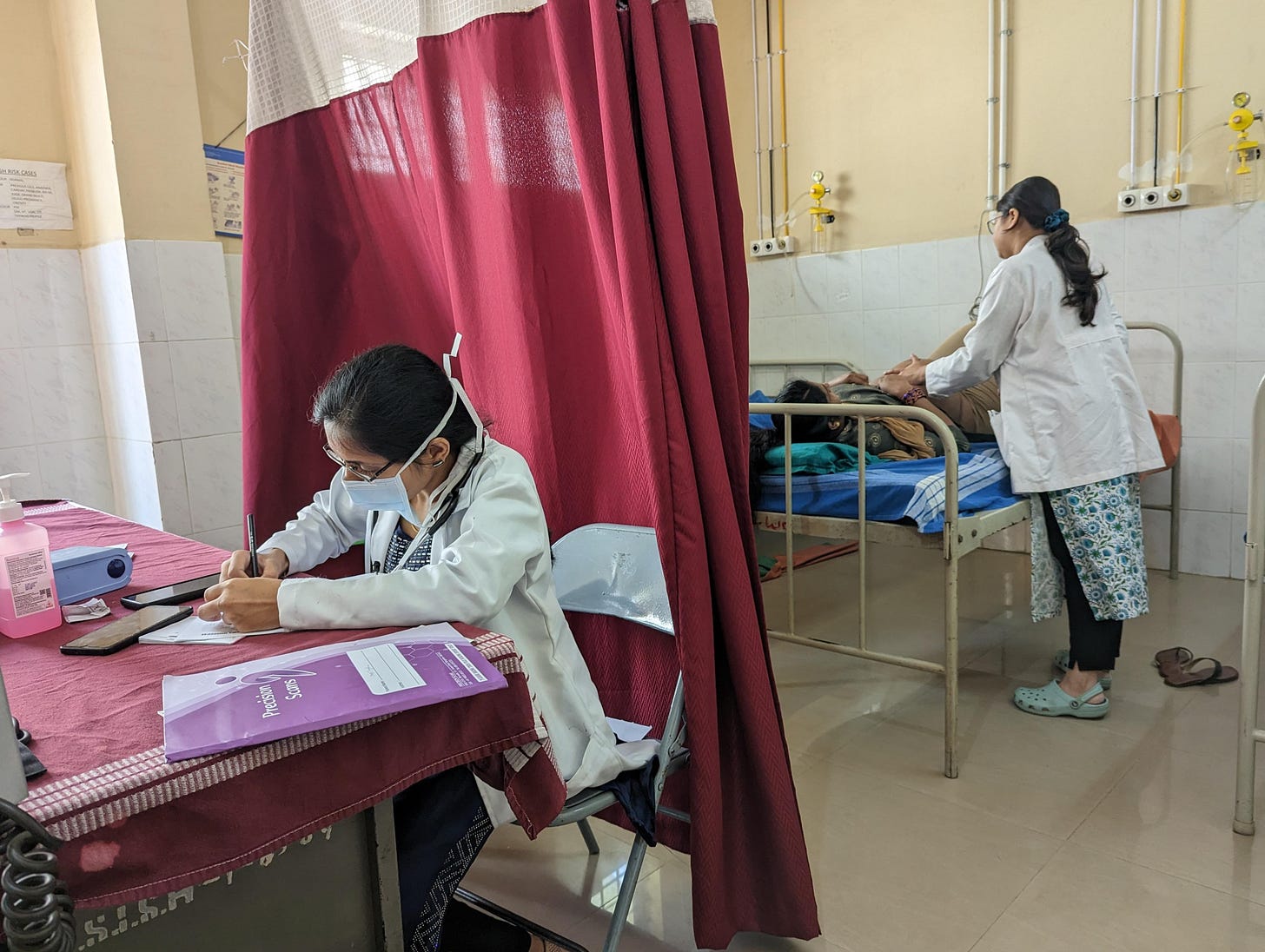

In this longform story, I reported on how some states are training doctors and nurses to look for the signs and symptoms of violence. This is not enough. These hospitals also need to provide referrals to counsellors and lawyers, and respect the patient’s privacy. Read how this is being done in Karnataka and Maharashtra.

Read: How Hospitals Are Helping Combat Violence Against Women | Scroll.in

Do we have the money to train everyone?

Yes.

After 2012 Delhi rape case, the Indian government launched the Nirbhaya Fund and puts Rs 1000 crore in it every year. But guess what–most of the money remains unused. Data journalist Shreya Raman and I analysed the data–here is a quick look at what the fund usage looks like.

Read: India Lacks a National Policy To Strengthen the Health Response for Gender-Based Violence | Missing Perspective X The Wire Science

Moreover, the inter-ministerial committee that oversees the Nirbhaya Fund, which is supposed to be for survivors of gender-based violence, has no representation from the health department. The Fund doesn’t actively finance any training for hospital staff to treat and care for survivors. We also have an analysis of how the funds are used (or not!).

We also examined the poor implementation of India’s policy for health system response to sexual violence, the lack of budgets for implementation such policies and training of doctors. We also looked at the attitudes of men and women to healthcare access–in effect how India failed to utilise an opportunity provided by the Nirbhaya Funds to support those who suffer from violence.

But aren’t the one-stop crisis centres created under the Nirbhaya Fund the intervention we needed?

Nope.

The One Stop Centres–also called Nirbhaya or Sakhi Centres–are not really hospital-based crisis centres. While they share premises with hospitals, they don’t work with doctors or nurses. The OSC staff’s understanding of health impacts is poor, and they get most of their referrals from the police. What survivors need is someone who places their mental and physical well-being front and centre, and then talks to them about reaching out to the police or shelter homes. They need to be given moral and psycho-social support first.

For that hospital staff need to be trained, and the OSCs need to know how to work with the hospital, not parallelly. There are 733 OSCs but very few actually work with the hospitals. In this podcast episode, I looked at one OSC in Maharashtra that goes out of its way to work with the hospital. The difference here was that the Medical Superintendent of the hospital was actively involved in making sure this collab happened. That is not the case with most OSCs. Listen to this episode.

What women want - Can Nirbhaya Centres do better to respond to gender violence? | Suno India

How do we understand what women's needs are?

It’s difficult, but not impossible.

Survivors of domestic abuse have different ways of seeking help depending on where they are and which socio-economic group they belong to. Take women in villages versus urban areas. Both groups have different health needs and patterns of health-seeking behaviour. In cities, women are more mobile and can access government city hospitals, where counselling centres and OSCs are often located. But such hospitals and facilities are far away from villages, so help and healthcare is not easily accessible to survivors of abuse here.

In this story from Patan, Gujarat, I explored what a health system response to domestic survivors from villages can look like. The key is identifying gender-based violence in villages early, together with counselling services at the lowest levels and support by ASHAs.

Read: How India’s public health system can reach rural women suffering domestic abuse | Missing Perspective X The Wire Science

With this series, I hope we find new ways of talking about violence–to each other and as a society–that also account for survivors' needs. Outrage against perpetrators is important, but even more important is ensuring that survivors are loved and cared for.

This is it for this edition. If you’d like more of TK–a mix of a journalist’s diary, reporting bloopers, outtakes from my stories, and research notes–do share and subscribe to this newsletter. If anyone’s interested in knowing more about pitching, grants and fellowships, you can write to mhmajain@gmail.com.

I will be back at the end of the year!

Best,

Mahima Jain